“A grand performance of a new work” is how a prominent Viennese musical newspaper announced a concert of music by Beethoven. Another paper wrote that “anyone whose heart beats warmly for greatness and beauty will surely be present.”

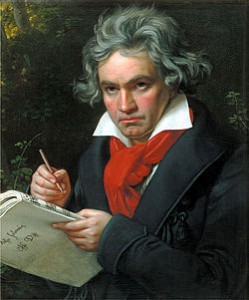

It was on May 7, 1824 that Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony was first performed. The symphony was remarkable for several reasons. It was longer and more complex than any symphony to date and required a larger orchestra. But the most unique feature of “The Ninth” was that Beethoven included chorus and vocal soloists in the final movement. He was the first major composer to do this in a symphony.

It was on May 7, 1824 that Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony was first performed. The symphony was remarkable for several reasons. It was longer and more complex than any symphony to date and required a larger orchestra. But the most unique feature of “The Ninth” was that Beethoven included chorus and vocal soloists in the final movement. He was the first major composer to do this in a symphony.

Beethoven actually started thinking about setting Friedrich Schiller’s “Ode to Joy” poem to music as early as 1793 when he was 22 years old. Over the following years, the composer would return to this text occasionally and sketch some possible themes for it, but no music was completed. Of course, the “Ode to Joy” has become one of the most recognized melodies in all of music

A Choral Finale

In 1817, the Philharmonic Society of London commissioned Beethoven to write a symphony, but he did not start serious work on the new piece until 1822. The first three movements were for the orchestra alone, but the composer knew he needed to end the work with something special. This is when he recalled Schiller’s “Ode to Joy” poem. A movement based on this famous melody was exactly the ending his new symphony needed.

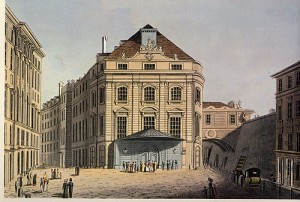

Although it was commissioned by an organization in London, influential Viennese citizens convinced Beethoven to present the first performance in Vienna. The orchestra of the Kärnnertor Theater had to be supplemented with additional musicians, and a chorus of 90 was needed to balance the strength of the orchestra.

Jumping Around Like a Madman

By 1824, Beethoven was almost entirely deaf, but still wanted to be part of the performance and was on stage while the piece was performed to indicate the tempos. Yet, Beethoven could not resist “helping” the musicians on stage by showing them the style and dynamics that he wanted.

The Kaerntnertor Theater in Vienna was where Beethoven’s Ninth was performed for the first time. The theater no longer exists. Today, on the site of the old theater is the Hotel Sacher, right behind the Vienna State Opera House.

The great composer’s actions were animated to say the least. One musician wrote, “he stood in front of the conductor’s stand and threw himself back and forth like a madman. At one moment he stretched to his full height, at the next he crouched down to the floor. He flailed about with his hands and feet as though he wanted to play all the instruments and sing all the chorus parts.” It was a good thing that the conductor had already instructed the musicians not to pay attention to the composer!

Unable to Hear the Applause

Beethoven’s deafness created one of the most touching stories in music. When the symphony was completed, he remained facing the orchestra and could not hear the thunderous applause of the audience for his new symphony. Caroline Unger, the mezzo-soprano soloist, had to tap the deaf composer’s arm and have him turn around so that he could see how the crowd’s response. Many of those in attendance, including Miss Unger, had tears in their eyes when they realized the extent of Beethoven’s deafness.