In Part 3 of this series, we saw how the festival had a rather rocky start. In Part 4, we will see how Franz Rehrl strengthened the festival, and then how the festival dealt with the Nazi influence before and during the war.

Franz Rehrl’s plan for the development of the festival

Following a rather difficult first few years, it was obvious that the festival would need new direction if it was going to succeed, and Franz Rehrl, the Provincial Governor of Salzburg, supplied that leadership. Rehrl was an astute politician and was able to lobby for the festival (in Salzburg and Vienna) with great success. Although his strength was not in cultural affairs, he has a fervent desire to see the festival succeed. And he realized a very important sequence of events for the festival: great culture would attract well-heeled visitors, and this would result in thriving business for Salzburg. This is still the case today.

Under Rehrl’s leadership, there were many changes to the festival: it became sponsored by the Salzburg government instead of relying on private donors from Salzburg and Vienna, the Winter Riding School was renovated as a stage for Reinhardt’s productions, and serious discussions to build a festival theater were resurrected. As the plans for the 1925 festival were taking shape, the organizers still did not have enough money to meet the Vienna Philharmonic’s financial demands. A letter to Austria’s Minister of Education stating that the festival would instead hire a German orchestra was what it took to get the Philharmonic to agree to the festival’s offer.

Something positive for Austria

Thirty-eight thousand people attended the 1925 festival, delighting in plays, operas, orchestral concerts, and chamber music. The New York Times reported that “the little mountain town is filled to overflowing with visiting celebrities, including former royal princes, American beauties, international film stars, actresses, singers, and world-famous orchestral conductors.” It was, however, the Neue Freie Presse who captured the achievement of the festival in the larger context of post-war and post-monarchy Austria: “We are used to a life which brings us unhappiness…finally something positive has been created…the Austrian Festival in a troubled time is something that we will treasure with joy”.

This year, 1925, was a turning point for the Salzburg Festival. The political squabbling and money troubles persisted for a few more years, and Hofmannsthal died, but the festival continued to grow. Bruno Walter and Clemens Krauss were frequent conductors and, although Jedermann was still performed each summer, musical performances began to overshadow spoken plays. By 1930, it made significant profits for the first time.

The Nazi influence

In the 1930’s, two forces made their impact on the festival: the early movement of the Nazi party, and Arturo Toscanini. The Depression was the political backdrop that led to the rise of Adolf Hitler. Many Jewish musicians from Germany fled to Salzburg, where they could perform in freedom. When the Nazis tried to establish influence, the party was banned both in Salzburg and in all of Austria. The German response was to levy a 1,000 Mark tax on any German citizen travelling to Austria, resulting in decreased attendance in the 1933 festival.

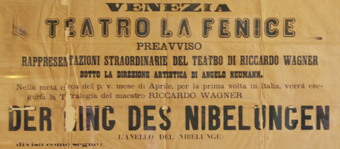

Toscanini’s arrival at the festival in 1934 did much to counteract the negative impact of the Nazis. He was the spotlighted conductor just when the Germans convinced Strauss and Furtwängler to cancel their appearances in Salzburg. The maestro also took a political stand: he would not conduct in Bayreuth when Jewish musicians were being mistreated. Bayreuth’s loss was Salzburg’s gain. Over the next several years, the festival was a financial as well as a critical success.

After the Anschluss, the Nazis tried to infuse Salzburg with Germanic history. Goebbels’s bust was installed where Rehrl’s once was, street names were changed, and the Germans took over the festival as a propaganda tool. One of their goals was to remove the international flavor that had flourished during the Toscanini years. Still, except for no production of Jedermann, the 1938 festival was little changed from what it would have been without the Anschluss. Hitler attended the 1939 festival, and the wartime festivals were smaller and less ambitious. The Ministry of Propaganda even renamed the event as “The Salzburg Summer of Music and Theater”.

In Part 5 of this series, we will learn about dynamic leadership of Herbert von Karajan, and further developments that has taken the festival to where it is today.