The most famous annual concert worldwide is the New Year’s Concert. This performance of the Philharmonic features the celebrated dance music – mainly waltzes and polkas – of the Strauss family. It is now broadcast around the globe and has come to showcase Vienna to an international television audience.

The first time Johann Strauss Jr. directed the Philharmonic was on April 22, 1873 for the Vienna Opera Ball, then held in the Musikverein. Strauss wrote Wiener Blut for the occasion. The master of the waltz only conducted the orchestra a few times, the last of which turned out to be tragic. He guest conducted the Overture to Die Fledermaus at the Court Opera on May 22, 1899, and caught a cold which turned into pneumonia and took his life less than two weeks later.

For all its popularity today, Strauss’s music was rarely played by the orchestra at the beginning of the twentieth century. Things began to change in 1921, when Arthur Nikisch conducted three waltzes to coincide with dedication of the famous statue in the Stadtpark. Then in 1925, to celebrate the hundredth anniversary of Strauss’s birth, Felix Weingartner conducted An der schönen blauen Donau (On the Beautiful Blue Danube) at two subscription concerts and also led an all- Strauss concert.

From 1929 to 1933, Clemens Krauss led an annual series of concerts of music by the Strauss family. In what has become the New Year’s Concert, Krauss conducted a “Special Concert” on December 31, 1939. The next year the concert was moved to January 1 with a repeat performance the following day. Finally, the name “New Year’s Concert” was used in 1946, and, except for two years, Krauss led these performances until his death in 1954.

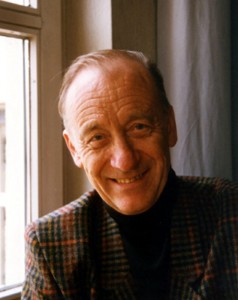

After much debate and discussion, the orchestra chose Willi Boskovsky to take over these concerts. Boskovsky led the New Year’s concerts for 25 years. For many, these were the golden years of these concerts. Boskovsky was the concertmaster of the Philharmonic and directed the orchestra just as Strauss himself had done – with violin in hand. He also had a charming personality that helped make these concerts into charmingly nostalgic excursions into Vienna’s past.

It was during Boskovsky’s tenure that the concert was first broadcast live on television, turning what had been a local concert into a worldwide media event. Following the Boskovsky years, Lorin Maazel was chosen to direct the concerts, which he did through 1986. Since 1987, a different renowned conductor has been invited to direct each year.

There are now three concerts: the Preview Performance on December 30, the New Year’s Eve Concert, and the New Year’s Day Concert.

As might be expected, tickets for these concerts year have become highly prized. Up to a few years ago, a letter requesting tickets had to arrive in the Philharmonic’s office on January 2, not before or after.

Today, requests are made via the Vienna Philharmonic’s website, and the period for applications for next year’s concerts is from February 1 through February 28. The “winners” are then chosen at random.