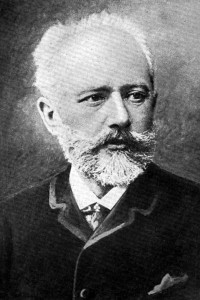

When is Tchaikovsky not Tchaikovsky?

Tchaikovsky

Pyotr Tchaikovsky is certainly one of the best known composers we hear these days. His “1812 Overture”, “Swan Lake”, late symphonies, and, of course, “The Nutcracker” are staples of the orchestral repertoire. But one of his wonderful works, the “Variations on a Rococo Theme” for cello and orchestra, is not entirely by the great Russian composer. This makes for an interesting and somewhat bizarre story.

Wilhelm Fitzhagen was a cellist who played in the premieres of Tchaikovsky’s string quartets and knew the composer’s music well. When he wanted to add to the repertoire of the cello, he decided to ask Tchaikovsky to write a work for cello and orchestra.

An Homage to Mozart

Tchaikovsky accepted the request and decided to write a work that paid homage to his favorite composer, Mozart. The work was to have a classical sensibility and use one of Mozart’s characteristic devices, a theme and variations. Tchaikovsky wrote a theme in Rococo style, and used this as the basis of his new piece.

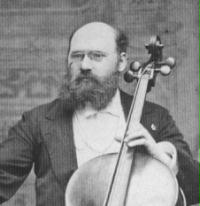

Wilhelm Fitzhagen

The composer worked on the variations between December 1876 and March 1877. When the music was completed, Tchaikovsky was quite pleased with his effort, and felt that he had indeed captured the lightness and classical style of his beloved Mozart. But the music Tchaikovsky had finished is not what we hear today!

What happened next is a bit strange. Tchaikovsky gave the music to Fitzhagen for the cellist to learn the piece. In situations like this, it is typical for the first soloist of a concerto to make some minor edits which make the work more playable. This happens when a composer does not know the instrument well and writes some things that are awkward to perform. This has happened dozens of times in the history of music.

Taking the Scalpel to the Music

Fitzhagen, however, was not content with making a handful of minor edits. He felt that he could make the piece much better than what Tchaikovsky had written. So instead of “tweaking” the music, the cellist decided to perform the equivalent of transplant surgery on it by reordering the variations, splitting an original variation into pieces and inserting them in different portions of the piece, and even omitting the music Tchaikovsky had originally intended to be right before the ending!

Unfortunately, Tchaikovsky knew nothing about any of this because he was abroad recovering from a short but painful marriage. And when he was away, Fitzhagen took the “revised” version of the variations and presented the work to a publisher named Jurgenson, claiming that Tchaikovsky had asked him to make the alterations. Jurgenson must have felt something was amiss, and wrote to the composer stating “Horrible Fitzenhagen insists on changing your cello piece. He wants to ‘cello’ it up”.

“Wrong” Music Published

After this, one would expect that the publisher would not have paid too much attention to the cellist’s version. But, incredibly, Jurgenson went ahead and published the variations with all the modifications that Fitzhagen had made.

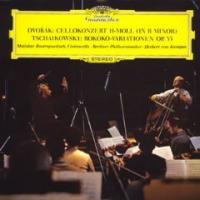

A classic recording of the piece

Tchaikovsky was livid with the situation, but did not take the publisher or Fitzhagen to task. Still, his irritation about what happened to his music remained for quite a while. Eleven years later, one of his students approached the composer and asked if Tchaikovsky would ever want to restore the piece to what he had originally written. The composer’s response was blunt: “Oh, the hell with it! Let it stay the way it is”.

What are we to make of the music today? One must actually give some (more than some?) credit to Fitzhagen, because the “Variations on a Rococo Theme” is a beautiful piece of music, and one that has charmed audiences for decades. It is one of the staples of the repertoire for cello and orchestra. Apparently Fitzhagen knew what he was doing in the first place.

But don’t tell Tchaikovsky that I said that.

It’s also fun to experiment with a long exposure to show the train in motion. Be sure to get to the end of the platform where the train will arrive moving quickly and show down your shutter speed. This shot used a quarter second exposure and a rear-curtain flash – you can see the driver as if he is not moving.

It’s also fun to experiment with a long exposure to show the train in motion. Be sure to get to the end of the platform where the train will arrive moving quickly and show down your shutter speed. This shot used a quarter second exposure and a rear-curtain flash – you can see the driver as if he is not moving. Hopefully tomorrow the weather will allow for some outdoor photography. But if it doesn’t, I guess I’ll just have to get wet.

Hopefully tomorrow the weather will allow for some outdoor photography. But if it doesn’t, I guess I’ll just have to get wet.