Last night, I heard Sir John Eliot Gardiner with his Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique and Monteverdi Choir play an all-Beethoven program: “Calm Seas and Prosperous Voyage” and the Ninth Symphony. The concert was in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. The orchestra has made Chapel Hill the first stop in their United States tours last year and this year.

Last night, I heard Sir John Eliot Gardiner with his Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique and Monteverdi Choir play an all-Beethoven program: “Calm Seas and Prosperous Voyage” and the Ninth Symphony. The concert was in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. The orchestra has made Chapel Hill the first stop in their United States tours last year and this year.

Hearing Gardiner conduct Beethoven with this orchestra is a treat. Because they play on period instruments (or replicas of period instruments), the sound is not nearly as smooth as we are used to hearing from ensembles that perform on modern instruments. This lends a certain roughness to the tone in some parts, and added sweetness in others.

Gardiner’s interpretation is based on the sounds of the instruments during Beethoven’s day, and he truly exploits the “less refined” characteristics of the sound. In a pre-concert talk, the orchestra’s first horn, Anneke Scott, commented on how Sir John does not ask horns to play softer as many conductors do. And Gardiner responded by saying that he wants more and more of the horn sound. Anneke smiled.

The Ninth Symphony is a wonder in almost any performance. What I appreciated about hearing it last night were the extremes that Gardiner manifested. The orchestra created a beautiful, soft tone in the strings in the third movement – must softer and warmer than is usually heard on modern instruments. This was almost ethereal, thanks to the gut (not metal) strings of the instruments.

At the opposite side of the spectrum was the timpani, which the maestro had play “full bore” in the opening measures of the fourth movement. One usually hears the timpani supporting the woodwinds and brass in these measures, but last night, the timpani practically dominated the sound. The resulting sound was fiery and intense. These measures always strike me as the chaos – the opening of the earth, if you will – that needs to be present in all of us before we can find joy.

Gardiner also had the orchestra and choir do some unique “staging”. The individual sections of the choir stood before they sung: the basses stood first, followed by the higher voices. He also had the piccolo player stand during the exposed solos passages. Not only that, but the piccolo was seated not with the flutes but next to the contrabassoon, the percussion, and in front of the basses in the choir. This makes perfect sense when one hears the Turkish March. This stuck me as such a fresh way to perform the work.

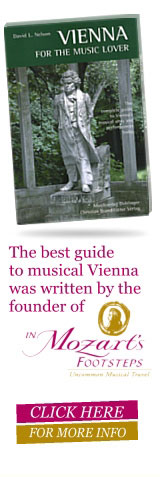

Finally, Sir John is a friendly and warm man. During the pre-concert talk, he was genuine and sincere in his discussion of the music. I took the liberty to walk on to the stage after his talk to introduce myself and give him a copy of my book as a “thank you” for his wonderful music making. (The book does have a picture of a famous Beethoven statue on the cover!) He was truly gracious and appreciative.