Some works in the history of music have clear stories that relate to their composition. Mozart’s Requiem and his final illness and death, Beethoven’s anger at Napoleon and the Eroica (Third) Symphony, and Dvorak’s time spent in Iowa and his New World (Ninth) Symphony come to mind. But the history of Shostakovich’s First Cello Concerto cannot be so easily categorized. In fact, the stories of its composition range from a light tale to the dark days of Russian history.

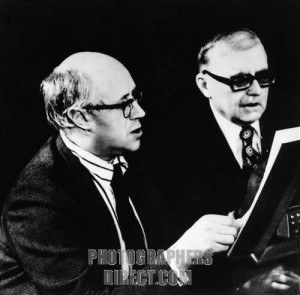

Cellist Mstislav Rostropovich was a great fan of Shostakovich’s music, and the two friends frequently performed chamber music together with the composer playing piano. The cellist was looking to expand the repertoire for his instrument and wanted Shostakovich to compose a concerto for the string virtuoso to play on his international tours. But he did not know how to broach the subject with the composer.

Enter Mrs. Shostakovich

With some savvy thinking, Rostropovich thought it would be a good idea to ask Shostakovich’s wife, Nina Vasilyevna, what she thought. The cellist later remembered their conversation: “Nina Vasilyevna, what should I do to make Dmitri Dmitriyevich write me a cello concerto?” She answered, “Slava (Rostropovich), if you want Dmitri Dmitriyevich to write something for you, the only recipe I can give you is this—never ask him or talk to him about it.'”

Of course the wife knew best, and a while later, Rostropovich read in the morning newspaper that Shostakovich had indeed written a cello concerto. Later that day, the composer asked if he could dedicate the work to the cellist, and Rostropovich immediately and humbly agreed.

As is often the case with premieres, the schedule leading up to the first performance was somewhat rushed. Shortly after he received the score, Rostropovich met with the composer to play the new work for him. Shostakovich searched his dacha for a stand to hold the music, but the cellist said no stand was needed. He had memorized the work in four days!

Some Dark Days of Soviet Russia

The concerto was composed in 1959 during a period when the Soviet rulers exerted great control over the actions of its citizens. Shostakovich once said that he was forced to read an official speech “like the paltriest wretch, a parasite, a puppet, a cut-out paper doll on a string.” Another composer commented that “the circumstances Shostakovich lived under were unbearably cruel, more than anyone should have to endure.”

How can a composer exist in such an atmosphere and still be creative and prolific? One of the ways that Shostakovich survived was to use satire in his music as an attempt to mock the Soviet leaders. In the Cello Concerto, he took part of Stalin’s favorite song, “Suliko”, and buried it in the fourth movement. It was so well hidden that Rostropovich did not even recognize this song until the composer carefully pointed it out to him.

Mocking Stalin

One would think that using Stalin’s favorite song would be an honor to the leader. That was certainly not the case here as Shostakovich had already used this music in a cantata to “caricature the Little Father of the People”, as one reviewer wrote. Another social commentator described the music as “gaunt, harsh, and rhythmic, and could very well bear the imprint of hints of the terrible years in Shostakovich’s life.”

Today we have a work that Mrs. Shostakovich told Mstislav Rostropovich to wait for, but in which Mr. Shostakovich did not wait to embed his mockery of the Soviet authorities. Thankfully, performances of it today are a long way away from the darker days of Soviet Russia.

This program note first appeared in Greensboro, North Carolina’s News and Record on October 17, 2010.