When asked which of his own operas he liked best, Gioachino Rossini wishfully said “Don Giovanni”. When Tchaikovsky looked at Mozart’s manuscript for the opera, he commented that he as “in the presence of divinity”. Charles Gounod claimed that “Don Giovanni” was “a work without blemish, of uninterrupted perfection.” Gustave Flaubert, author of “Madame Bovary”, believed that “Don Giovanni, Hamlet and the sea were the three finest things God ever made.”

There are many reasons for such admiration of the “Don Giovanni”. Certainly, Mozart was at the peak of his creative ability when he fulfilled this commission for the Nostitz (now Estates) Theater in Prague, and his three collaborations with librettist Lorenzo Da Ponte (“Marriage of Figaro”, “Don Giovanni”, “Cosi fan tutte”) are among opera’s finest creations. Of course, the

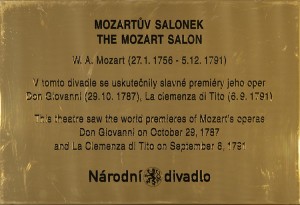

Plaque inside the Estates Theater saying that "Don Giovanni" and "La Clemenza di Tito" were first performed there.

“Don Juan” story—the downfall of a serial womanizer and the inability of a person to change for the better—is a tale that has had universal appeal and numerous settings. (Incidentally, Da Ponte may have had some extra insight into the lead character as he was friends with Casanova in Venice.) Finally, the opera mixes serious and comic elements to perfection.

What gives Don Giovanni its timeless value and makes it a superior musical work is not only the subject matter or the balance between the comic and the serious; it is Mozart’s absolutely brilliant portrayal of the inner emotional states of each character through his music. It is as if Mozart could look directly into the soul and psyche of each person on stage and then create the melodies and harmonies to give the audience an uncanny view into this character’s most intimate feelings.

This is most readily apparent in the music sung by Don Giovanni himself, which mirrors the twists and turns of his complex personality as the story unfolds. When Giovanni is confronted by the Commentadore in the opening scene, Mozart’s music depicts the lead character as somewhat reluctant to engage the distinguished older gentleman, but then the music morphs to expose the a more aggressive side of Giovanni as he is unwilling to walk away from the conflict. The most important conflict of the opera is enhanced by Mozart’s music.

A contrasting side of the same character is shown as he attempts to show his trustworthiness and gentle nature in his romantic pursuits of Zerlina in Act 1 and Donna Elvira’s maid in Act 2. In the duet with Zerlina (“La ci darem la mano”), Giovanni invites his “prey” to overcome her resistance until the two sing together before leaving the stage. In “Deh, vieni”, the cloaked leading man shows his mandolin-playing prowess in another attempted seduction. His excitement for an upcoming party comes out in spades in the fast and exuberant “Champagne Aria” in which he claims his list of female conquests will be enhanced by at least ten “by tomorrow morning.”

The auditorium of the Estates Theater is unusual because it is in blue. A administrator told David Nelson that they chose that because Prague "had seen too much red" referring to the communist era.

The absolute core of Don Giovanni’s character does not come out until the end of the opera when the Commentadore comes back to life as the Stone Guest and challenges Giovanni to repent and give up his philandering ways. Mozart gives us the most dramatic music of the evening, bringing back the solemn introduction and angst-filled scales from the beginning of the overture. Against the insistency of the Stone Guest with his ominous, unchanging melody and Leoporello’s humorous, fast interjections, is the main character’s steadfast resolve not to change. When the music reaches a fever pitch, Mozart increases the tempo and adds chorus. Still, Giovanni refuses to relent, and his emphatic “No’s” become even more insistent until he is finally dragged down—physically and musically—to the gates of Hell. If one thinks this is powerful music today, imagine how it must have affected audiences in 1787.

Mozart’s portrayal of the other characters is just as rich. Don Ottavio’s overly accommodating personality, as he continues to wait for his beloved Donna Anna to finish her seemingly never-ending grieving, comes out in his two solo arias.

Leporello’s clumsy yet humorous attempt to pacify the angry Donna Elvira by telling her of all 2,065 of Giovanni’s romantic conquests (so far) is presented in the intentionally over-the-top “Catalogue Aria”. (Listen to how the “male” low strings chase the “female” upper strings as the music begins.) The peasant character of Zerlina is beautifully reflected in the simple “Batti, batti”, and her “Vendrai Carino” is one of the most moving depictions of pure love ever written.

“Don Giovanni” is an opera that works on many levels. It has a timeless story, beautifully developed characters, and a wonderful text. But the words coming from the stage can only tell us so much about each personality. It is Mozart’s inspired music that highlights the inner nature of each character in ways that no libretto ever could.