In 1820, Prince Esterhazy ordered that Haydn’s remains be transferred from Vienna to Eisenstadt. One of the biggest surprises in all of music must have been when the coffin was opened and Haydn’s skull was missing. The story of the missing skull proves that truth is stranger than fiction.

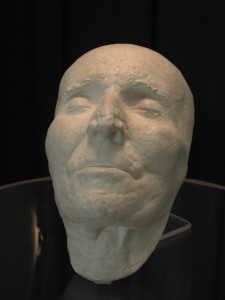

Franz Joseph Gall was a scientist who believed that a person’s intellectual characteristics were defined by the size, shape and proportions of their skull. Two of Gall’s followers were Joseph Carl Rosenbaum, a close friend of Haydn, and Johann Nepomuk Peter. They bribed the gravedigger, and, just four days after Haydn’s death, opened the grave at night and stole the composer’s head. Later they justified their action by saying that they could not see such a magnificent spirit lay in the ground being eaten by maggots and worms.

In the examination that followed, Peter claimed to have found “the seal of hearing, just as it is given in the preface to Gall’s book.” Following that, Rosenbaum kept the skull “on a cushion covered with while silk and draped with black satin inside a black wooden cabinet that was modeled after a Roman sarcophagus and decorated with a golden lyre.” And this was kept in a mausoleum in his yard for visitors to see. One of the ironies is that Joseph Rosenbaum’s wife, Therese, sang at the memorial for Haydn on June 2, 1809.

The story gets stranger. After the skull was discovered missing, the authorities unsuccessfully searched Rosenbaum’s home. Mrs. Rosenbaum had hid the skull under her mattress, and then lay down on it. She claimed that it was “that time of the month.” Then after Prince Esterhazy paid Rosenbaum for the skull, one skull and then another—neither belonging to Haydn—were presented. This meant that on December 4, 1820, a stranger’s skull was placed on Haydn’s remains.

Just before he died in 1829, Rosenbaum gave the skull to Peter, and when Peter died in 1839, his widow gave it to their physician, Dr. Karl Haller. Dr. Haller gave the skull to a Dr. Rokitansky, a Viennese Pathologist who stored it is the Pathological-Anatomical Institute of the University of Vienna. Rodakitansky’s successor was Professor Kundrat, who gave the skull back to Rokitansky’s sons, who finally presented it to the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde.

This bizarre story was finally resolved in 1954. In a ceremony at the Musikverein, the skull “was placed in an urn decorated with a golden laurel wreath surrounded by red and white peonies.” Then a large procession (100 cars!) drove past Haydn’s birth house in Rohrau and to the Bergkirche in Eisenstadt, where the skull was finally returned to its body.