Paganini was one of the world’s great virtuoso violinists. But what is especially fascinating is that part of Paganini’s great success came as a result of a rare physical ailment.

Niccolò Paganini was born in 1782 in Genoa, Italy. His father taught him mandolin at age five and violin two years later. Like many child prodigies, the boy’s musical talents were quickly recognized, and he began the serious study of the violin with a number of skilled teachers. By the time Paganini was eighteen he was well known around Genoa and Parma, and a decade or so later, the violinist had made a name for himself throughout Europe. When he died in 1840 in Nice, France, Paganini had established himself as one of the great masters of the violin.

Niccolò Paganini was born in 1782 in Genoa, Italy. His father taught him mandolin at age five and violin two years later. Like many child prodigies, the boy’s musical talents were quickly recognized, and he began the serious study of the violin with a number of skilled teachers. By the time Paganini was eighteen he was well known around Genoa and Parma, and a decade or so later, the violinist had made a name for himself throughout Europe. When he died in 1840 in Nice, France, Paganini had established himself as one of the great masters of the violin.

Pushing the Limits of the Violin

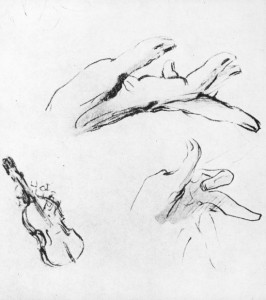

In his relatively short life, Paganini dramatically increased the technical possibilities of the violin. He could do what no one had ever done on the instrument. The virtuoso made left hand pizzicato and harmonics hallmarks of his style, and was even said to be able to play three octaves of notes across the four strings. Most violinists consider this impossible today.

But why could Paganini do these miraculous feats on the violin? Scholars have pondered this question for more than a century and a half, and many have come with the conclusion that the violinist had a little known medical condition called Marfan syndrome.

Marfan syndrome is a genetic disorder changes a person’s connective tissue, often making them unusually tall with lengthened limbs and long, thin fingers. Observers of Paganini frequently commented on his unique hands. In 1831, his personal physician wrote, “Paganini’s hand is not larger than normal; but because all its parts are so stretchable, it can double its reach. For example, without changing the position of the hand, he is able to bend the first joints of the left fingers –which touch the strings–sideways, at a right angle to the natural motion of the joint, and he can do it with effortless ease, assurance, and speed. Essentially, Paganini’s art is based on physical endowment, increased and developed by ceaseless practicing.”

An anecdote of Paganini’s unheard-of ability is especially telling. One night, a rich gentleman asked the virtuoso to serenade his lady friend. The air was quite damp, and the violin strings of the day did not respond well to this kind of humidity. First the “E” string broke. The violinist was not fazed. Then the “A” and “D” strings snapped. The older gentleman was instantly worried and feared that the serenade for his friend would be ruined. What did Paganini do, now that he only had one string to play on? He simply smiled and continued to play on one string just as if he was playing on all four. The serenade was a success after all, thanks to the virtuoso’s amazing ability.

Having Marfan syndrome also created a certain mystique for Paganini. People called him “Hexensohn” (“Witch’s Child”) because of his seemingly superhuman ability. Some claimed that he had made a pact with the devil to play as well as he did. Reports of his “demonic” possession were enhanced by the medical condition which made him appear unusually thin and pale.

Paganini loved all this notoriety and had fun with it. To accentuate the rumors, he would dress completely in black and sometimes arrive at a concert in a black carriage pulled by four black horses. And when he lost his teeth in 1828, his face looked even more ghostly. Of course, people flocked to his concerts. Some have even called him music’s first rock star.

Medical ailments are often viewed as things to overcome. With Paganini, Marfan syndrome actually enhanced an already considerable talent to help him become one of the world’s finest instrumentalists.

This column first appeared in Greensboro, North Carolina’s News and Record on January 9, 2011.